Upcoming Events

16 Dec 2025 | 06:30 PM - 08:30 PM

Patina Osaka Hotel

Get into the holiday spirit with the second ACCJ–Kansai Christmas Charity Bash! Join us for a night filled with cheer, community, and charity at the luxury Patina Osaka hotel.

19 Jan 2026 | 12:00 PM - 02:00 PM

Hamarikyu, Conrad Tokyo

Join the BCCJ for a retail market keynote and fireside chat with ALLSAINTS CEO Peter Wood on APAC consumer trends and the future of fashion in Japan.

27 Jan 2026 | 12:30 PM - 02:00 PM

The British Chamber of Commerce in Japan

An action-packed hour of in-person practice, coaching, and feedback to help you speak with more clarity, confidence, and impact as a woman in business in Japan.

Latest Initiatives

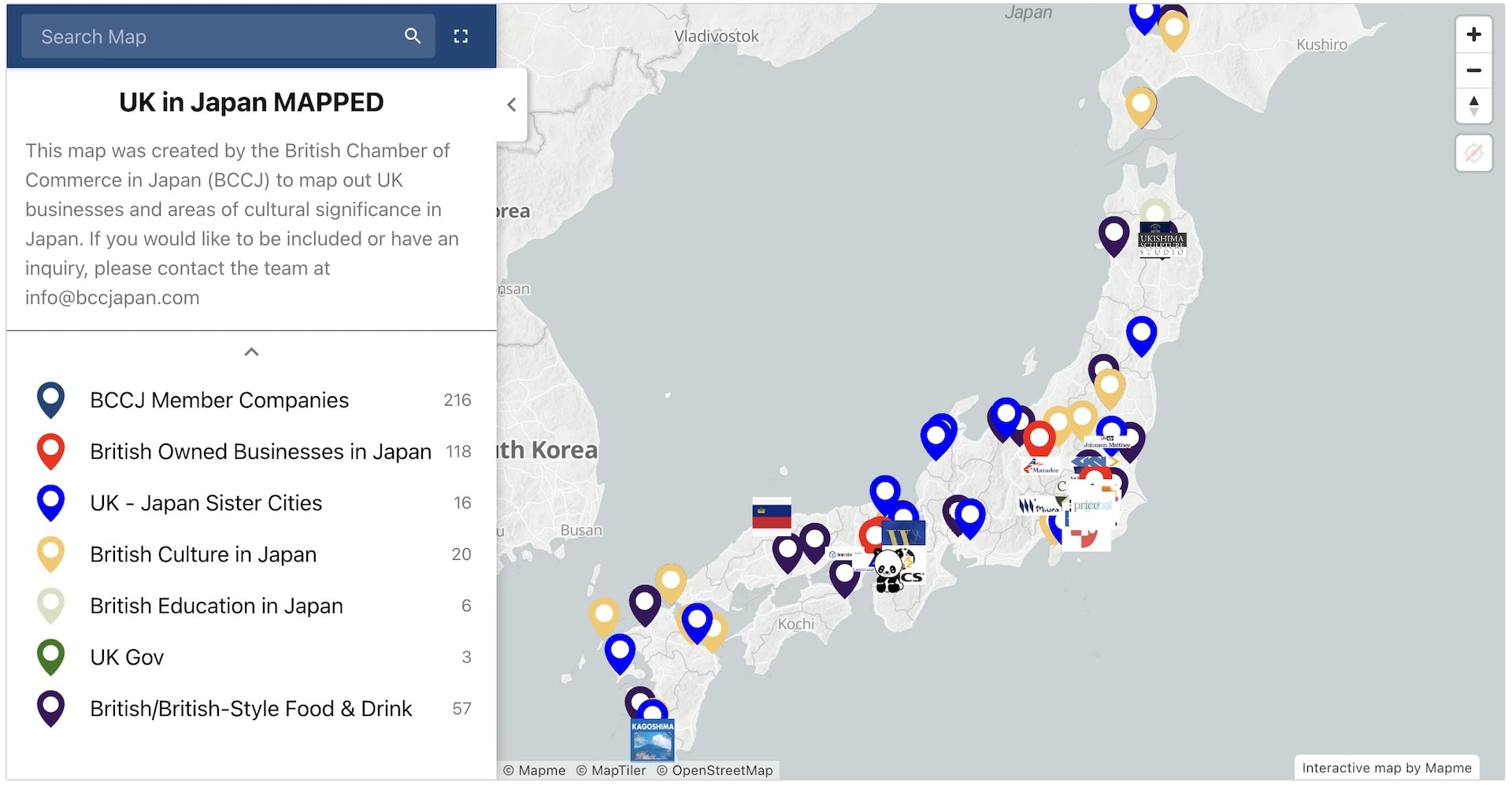

The BCCJ is based in Tokyo, Japan, however our approach to commerce and member-relations…

A World Expo is a global event that showcases the achievements of world nations whilst…

At the BCCJ, fostering Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is not just a commitment—it’s…

The British Business Awards is Japan's largest awards night of UK-Japan business and…

Latest News

UK-based accessibility technology firm Transreport Limited has been awarded the British…

A mere nine months since its establishment, Tokamak Energy KK has demonstrated an impressive…

The British Chamber of Commerce in Japan (BCCJ) is delighted to welcome Senator International…

Walk Japan, a travel company specialising in walking tours that take visitors to off-the-…