Member? Please login

Power Harassment in Japan – What You Need to Know

Written by Sterling Content

April 14, 2023

Past Event Round Ups

“Power harassment” (defined as a form of workplace harassment or workplace bullying) is the most common form of harassment in Japan, affecting as many as a third of the workforce.

A recent survey by management firm Shikigaku involving more than 2,200 respondents found that nearly 35% had experienced some form of harassment in the workplace, with no significant differences among men and women. Among those who had been harassed, power harassment topped the list (71% of those surveyed), followed by “moral harassment” (psychological harassment) at 43% and sexual harassment at 21%.

Only 36% reported the harassment to their company; most respondents said that doing so would not change the situation. Among those who did report the issue, 47% said their company did nothing in response.

Cases of harassment have been on the rise in recent years, and the result of inaction is damage to employees, the workplace and society, according to the media.

Tokyo-based newspaper Nikkei Asia reported in 2021 that complaints about workplace abuse have climbed to 88,000 cases a year, more than tripling in the past 15 years. Such cases include a “shocking video of senior elementary school teachers forcefully holding a junior colleague in the school and making him eat painfully spicy curry,” according to Kojima Law Offices. Another case reported by Nikkei Asia involved an auto engineer who committed suicide following harassment.

Employers now have a legal obligation to combat the issue or face the risk of court action due to new laws aimed at preventing such abuse. So, how can employers identify and put an end to power harassment?

Understanding the law

In May 2019, legal requirements were established in Japan for power harassment, with such measures becoming mandatory for large employers from June 2020 and for small and medium-sized enterprises from April 2022.

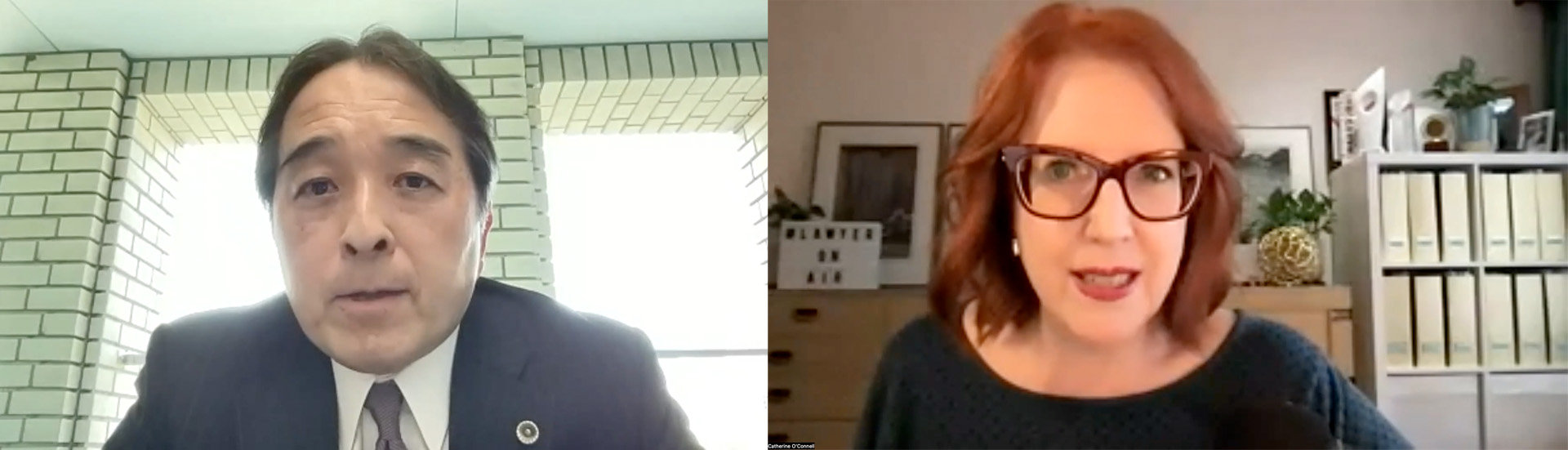

Against this backdrop, legal experts Hiroshi Chiba of Tokyo Uchisaiwaicho Law Firm and Catherine O’Connell of Catherine O’Connell Law offered members of the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan insight into the new legislation, which for the first time in Japan obliges employers to take preventive measures to stop workplace misconduct where there is a power differential.

According to Chiba, power harassment must be behaviour which meets three elements: that which constitutes bullying in the workplace; that which exceeds the scope necessary and reasonable in the course of business; and that which damages the work environment. Workers include hybrid and “non-regular” workers.

Such bullying could be carried out by a person with a higher position, a colleague or even a subordinate. Frequency and continuity are important factors in determining such power harassment, together with the physical and mental condition of the worker involved and their relationship with the offender(s).

Government guidelines issued in January 2020 describe examples of power harassment, such as physical assault, emotional abuse, isolation, excessive or insufficient work demands and invasion of privacy.

Chiba gave the example of a supervisor calling a subordinate on a holiday or forcing them to work overtime on weekends. Another example was scolding a subordinate in front of their colleagues, which in one case led to the suicide of an employee.

He also offered examples from court judgements, including a case where a female employee suffered a nervous breakdown after being bullied by her colleagues “for a considerable period of time and in a very insidious manner.”

Another court judgement related to a railway worker who was forced to transcribe the entire text of the company’s work rules, after his supervisor spotted him wearing a belt with a union mark in violation of company rules.

“Hot-blooded” bosses are also in the firing line, particularly those dealing with younger generations who may require a more communicative approach than older ones, Chiba said, adding that generational differences mean it’s important to ensure intentions are explained clearly to younger workers.

Power harassment can also occur in an online environment, such as workers being told to respond immediately to any emails, even those sent outside working hours, or being forced to attend frequent and “unnecessary” online meetings.

Legal liability

Although no clear legal criteria have been established for judging power harassment, Chiba said companies could be liable for compensation if they knew about such behaviour and failed to deal with it. Criminal liability exists for such crimes as defamation, insult, intimidation, assault or injury, including fines and possible detention.

Companies may face guidance from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and if appropriate action is not taken, the details may be made public along with the name of the company, in a form of public shaming.

“It’s important for employers to become familiar with those regulations. Saying you’re too busy or it’s HR’s job isn’t going to wash, and we’re all having to be responsible employers,” O’Connell said.

Asked about penalties, Chiba said it would depend on each case, with companies potentially facing large compensation should the affected worker be hospitalised.

Employers are also required to establish a mechanism whereby workers can report abuse, as well as protecting whistle-blowers.

Avoiding power harassment

Chiba provided guidelines for employers seeking to prevent power harassment:

• Understand the scope of power harassment

• Respond appropriately according to the subject’s personality and other factors

• Before reprimanding an employee, consider the method of reprimand

• Don’t get angry in public

• Don’t deny everything about your subordinate

• Follow up after getting angry

• Don’t ignore the employee

• Don’t lose your temper with dispatched workers or business partners