Member? Please login

A remarkable life bridging Anglo-Japanese cultures – Ichiro Urushibara

Written by Sterling Content

May 11, 2018

Japan News

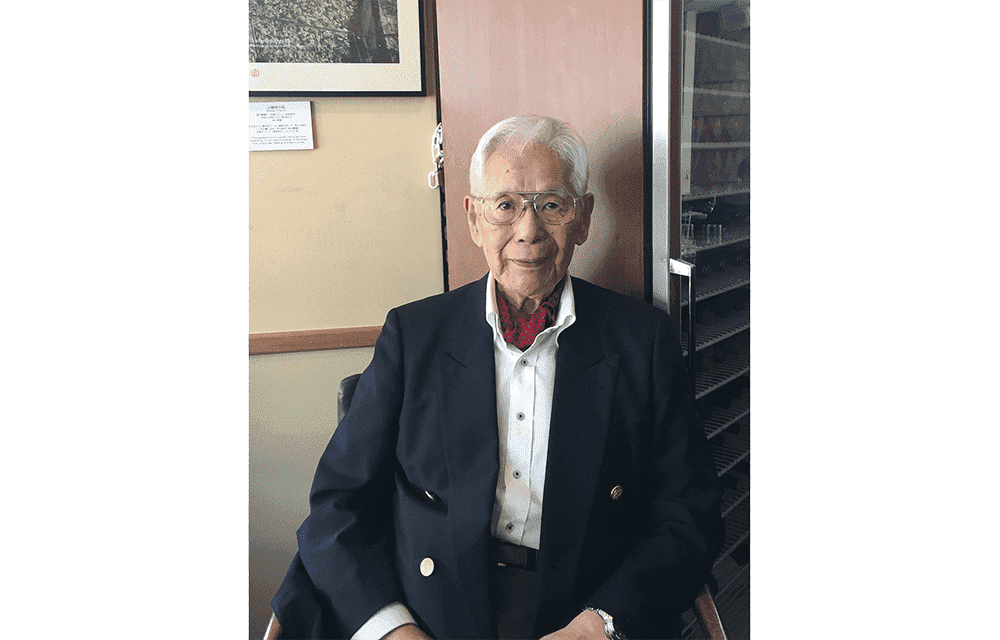

Eighty-seven-year-old Ichiro Urushibara may have spent only the first decade of his life in the UK, but the experience was the seed for a remarkable life in Japan—in media, commerce and international relations.

Though his curriculum vitae includes employment at some of Japan’s biggest corporate names and respected institutions, as well as involvement in overseas liaison activities, Urushibara’s early years were difficult.

Woodblock art heritage

Urushibara was born in London in 1930, the son of renowned woodblock artist Yoshijiro (Mokuchu) Urushibara, who had settled in the UK following his success at the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition of 1910. The largest international exposition in which Japan had participated, the event lasted more than five months and showcased not only Japan’s gardens, history and crafts but also its government ministries and modern systems.

Mokuchu was one of the woodblock print craftsmen who demonstrated printing techniques at the exhibition. Afterwards, he decided to remain in London and got a job restoring and making reproductions of prints at the British Museum, where some of his work is still displayed. He went on to develop his own woodblock prints, including of Stonehenge and other iconic UK landmarks, while working with famous British designers of the time such as Sir Frank Brangwyn.

“My father did all three components required for woodblock prints: the original picture, the carving and the printing,” says Ichiro, adding that the work intrigued artists, fused Japan and the UK and helped popularize the works of British artists among people who couldn’t afford pictures. Mokuchu even received a letter in August 1940 signed by then-prime minister Winston Churchill, who thanked him for his “delightful” woodcuts.

But trying to sell pictures during the Great War and the Depression in England and then World War II and the Occupation in Japan was a “very trying time, financially,” says Ichiro.

In 1940, at the recommendation of the Japanese government following Japan’s entry into the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis, the Urushibara family set sail to Yokohama from Ireland via Bermuda, New York, Panama and Los Angeles in a journey that would take more than two months.

Arriving “home”

Ichiro spoke only English and says he was “quite patriotically British” until he arrived in Tokyo aged 10 with his parents and sister.

“After surviving the Blitz in London, we were now at the receiving end of the American bombings, but we were lucky,” he says. One night, with their house surrounded by “red skies” he recalls the family attempting to flee but having nowhere to go. “One incendiary bomb was dropped on next door and we had to extinguish that. Then one fell on our hedge and I remember putting that out, but I wasn’t really frightened; I didn’t realise what it was all about,” he says.

In what Ichiro describes as a period of “anti-Western” sentiment, he had to have a “crash course” in Japanese before being able to enroll in school. “I was always mispronouncing or using the wrong word and being chastened for it. It was a confusing and not very comfortable time,” he says.

But Ichiro’s persistence paid off and, age 17, he found work utilising his fluency in Japanese and English as a publications examiner for the Civil Censorship Department. His role was to mark parts of newspapers and magazines that could be deemed in violation of General Douglas MacArthur’s press code and translate them into English.

During the Occupation, English skills were greatly sought and, after one year, Ichiro took a job with Time-Life International, driving around the many military bases in Tokyo delivering magazines.

At 20, he had to choose Japanese or British citizenship, opting for British as the passport was “far more useful for travel” and made him “a member of an occupation nation, with access to rations from special shops and access to imported goods.”

(Wood carvings from Ichiro’s father, Yoshijiro (Mokuchu) Urushibara in a pre-war Britain)

(Wood carvings from Ichiro’s father, Yoshijiro (Mokuchu) Urushibara in a pre-war Britain)

A colourful life

Opportunities continued to present themselves to the fledging translator, as many Japanese firms at the time were looking for materials in English. He also diversified into interpretation, radio DJ’ing, emceeing and announcing, including more than 20 years combined at Nippon Shortwave Broadcasting Co., and Radio Nippon.

Yet Ichiro insists that his career was far from planned. “There wasn’t so much competition in those days and there was a big demand [for English] in Japan,” he explains. “I was very fortunate because all the work came to me. Even my limited capabilities were of some use.”

He attributes his success to being “a rarity, in the right place, at the right time” and having a large variety of interests. His love of building radios and fondness for cars, for example, gave him a familiarity with technical terminology that led to work translating instruction manuals and editing the English language publication, Motor Magazine. He also interpreted at press conferences for Toyota Motor Corporation and was even a commentator at Fuji Speedway for international motorcar and motorcycle races.

Seeing Ichiro’s talent, coupled with his eagerness and ability to turn his hand to anything, organisations continued to vie for his time, resulting in both steady employment and freelance work.

In autumn 1968 he served as the bilingual master of ceremonies at British Week, an initiative supported by the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan and the British Embassy Tokyo, to show the UK’s history, technology, culture, sport, music and fashion.

Not long afterwards, he provided live simultaneous interpretation of the Apollo 11 space mission for Tokyo Broadcasting System, to cover man’s first steps on the moon. “Of all the channels showing the mission in Japanese, I was the only interpreter who could convert feet into meters,” he says.

After covering the missions until Apollo 17, he landed the job of interpreter for Antonio Inoki, the Japanese boxer who took on Muhammad Ali at Nippon Budokan, Tokyo, in 1976. “I remember meeting Ali at the airport,” he says.

Of all the colourful roles Ichiro held, he says the most challenging was being a simultaneous interpreter for the Japanese delegation at the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IU), which took him to 51 countries over an 18-year period.

On those trips he recalls shaking hands with Fidel Castro at the Japanese Embassy in Cuba and with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican. He was also present at the IU’s 100th anniversary celebration in London, in 1989, which was attended Baroness Margaret Thatcher LG OM and Queen Elizabeth II.

Though Ichiro admits he is finally slowing down, he remains keen to tell his story—of perseverance and positivity.